ArtsEtc Inc. 1814-6139

All works copyrighted and may not be reproduced without permission. ©2013 - hoc anno | www.artsetcbarbados.com

All works copyrighted and may not be reproduced without permission. ©2013 - hoc anno | www.artsetcbarbados.com

Racquel Griffith: How would you define your art?

Annalee Davis: My work sits at the intersection of biography and history, focusing on post-plantation economies by engaging with a particular landscape in Barbados. I am interested in drawing lines on paper, interfering with lines on ledger pages, exposing the awkward fullness of maternal and paternal family lines, forming lines that connect that time to this time. My practice recognizes the need to draw new lines—refusing to accept that all potential lines have already been drawn before.

RG: re: wilding is a captivating title. What prompted the decision to separate the word “rewilding” in this way?

AD: I was invited to be part of a group virtual exhibition called re:rural—four contemporary artists unlearn and reimagine the rural. The UK-based gallery Haarlem Artspace presented it as Haarlem Periodical, the gallery’s new, curated platform, to mark their fourth anniversary. Liv Penrose Punnett curated my solo show at the gallery, which ran concurrently, and I called it re: wilding in response to re:rural.

RG: What is the significance of the colour red in the Wild Plant Series?

AD: I chose this Victorian rose colour which mimics the hue of the rows and columns on the ledger page. It also references the blood that runs through our veins, something we all share.

RG: Your choice of paper showing plantation cash receipts and monetary figures for the backgrounds of F is for Frances and the Wild Plant Series is a unique one. Can you tell us how you came to find these papers and why you used them for these particular pieces?

AD: Over the past six years, I have been drawing on plantation ledger pages dating from the 1950s to the 80s which I found in an abandoned bookkeeper's office. As a substrate, they function like palimpsests, inferring order and control across the rows and columns in spite of the chaos inherent in the plantation as a historical reality. The ledger page speaks to the act of cataloguing and surveillance on the plantation, whereas my graphic interventions push back against fiscal narratives by inserting images that suggest other ways of reading the site.

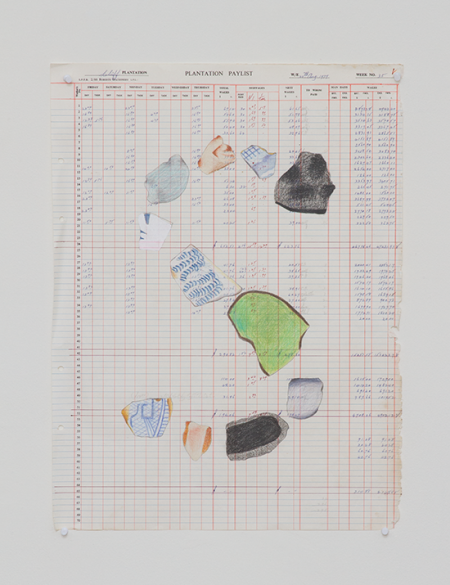

F is for Frances refers to the woman named in an 1815 will written by Thomas Applewhaite, the owner of Walkers—the site where I live and work. This suite maps Frances’ name across seven ledger pages. The letters comprise 18th- and 19th-century shards I found in former sugarcane fields, suggesting fragments of histories understood in part—usually through the words and gaze of the white male colonial settler. With Frances, another voice becomes audible and visible.

Wild Plant Series counters the conventional daily logging of economic plantation activity. Harvested from the fields, pressed and drawn, my inscription of these wild plants onto these pages is an attempt to decolonize the ledger by repopulating it with botanicals native to the island, exposing gaps in Barbados’ plantation history buried in the soil, in the public imagination, and inadequately documented in the archives.

F is for Frances (detail). Photo credit: Mark King.

RG: The year 2020 has brought about so much change in how we view and live our lives—whether we’re talking the Black Lives Matter movement escalating, the COVID-19 pandemic, our use of technology in new ways, and even how we view our physical, emotional and mental well-being. Could this be considered a revolution in some ways? What does/would your revolution look like in the context of 2020, your art, and your social conversations on race in Barbados?

AD: 2020 has undoubtedly been a profound year for all of us, and at the height of the BLM [demonstrations] I was engaging in many conversations about race and class. I was proud to be part of the Black Lives Matter march in Barbados on June 13th and see that the 2020 debate, building on decades of work, including a petition by young Barbadian historian Alex Downie, contributed to the recent removal of the Nelson statue in Bridgetown, suggesting our maturity as a nation.

Thanks to the pandemic and the opportunity it has provided us all for reflection, I have been ruminating on two terms—slow cultural work and degrowth. Rather than striving for more and bigger, how might we work and think differently, more sustainably, make time for relationships, make different choices while considering our perspectives here in the Caribbean, including asking what it means to undo colonialism and consider self-determination?

For me, the revolution means that we commit to decolonizing pedagogy, governance and cultural institutions. It means that we decolonize shame, imposter syndrome and trauma while shaping more inclusive spaces which value independent thinking and full citizenship.

In the arts, the ultimate revolution is investing in our artists. What role do the arts have to play in manifesting more equitable, happy and sustainable futures for Barbados and the wider region? How can a region born out of trauma, and then abandoned, be worth loving? Self-love in this historical and contemporary context—love for this small island and for one another—is where the real revolution is.

And if we want to decolonize love, we need to decolonize the falsity of family trees in the Caribbean, which favour so-called legitimate families while ignoring outside or “contaminated” relations.

RG: Can you give some insight into how your art project Leh We Talk: Real Conversations on Race and Class in Barbados is going this year?

AD: The US-based BLM movement and George Floyd’s murder provoked conversations in Barbados that we need to address through the lens of our particular context and history. I don’t imagine we’ll ever have a moment like this again and wanted to harness this collective heightened interest in and openness to discussing race and class. I wrote a post on my Facebook page called “On race and whiteness from the context of Barbados” and, soon after, launched Leh We Talk | Real Conversations on Race and Class in Barbados (LWT).

Act of revolution: Black Lives Matter demonstration held in June 2020 in Barbados.

I collaborated with Janelle Headley, the founding director of Operation Triple Threat, a Barbadian theatre company through which this inaugural discursive art project kicked off on July 18. A group of about forty Bajans and interested others gathered; on arrival, they were paired with partners of a different race. They engaged in intimate conversations, prompted by a menu of questions such as: When was the first time you were aware of your race/class or sensed you were different from others because of race/class? How have the forces of race, racism, class, and classism shaped your life? I hope to build on this in 2021.

RG: Do you see these conversations about race in Barbados as an extension of your art/artistic voice?

AD: I do. Conversation is an art form in and of itself, and I see LWT as a discursive experiment, making us more curious and open and [ready] to ultimately foster human connection. It is designed for participants to reflect on themselves while learning how to listen to others of a different race through questions focused on race, racism, class, and classism. My interest in the plantation and its vestiges in contemporary society extends to a preoccupation with how race is constructed and understood here in Barbados.

RG: Has your artistic voice changed/evolved since you started exhibiting your work in the early 90s?

AD: Many artists, I think, work with one or two ideas throughout their careers which are continually refined through the processes of thinking and making. As I move more deeply into ideas, unpeeling layers and continually exposing the subterranean minefield that is the plantation, the work is becoming more specific and, notably, more personal. In the last ten years, my work has also expanded into a hybrid practice to include writing and cultural activism through the Fresh Milk Art Platform, and collaborative regional projects [such as] Caribbean Linked and Tilting Axis.

RG: How does all this activity and the CATAPULT Lockdown Virtual Salons at Fresh Milk link together?

AD: Since 2011, Fresh Milk’s work has spanned creative disciplines, generations, and linguistic territories in the Caribbean through its local, regional and international programming, including: residencies, lectures, screenings, workshops, conferences, exhibitions, projects, etc. Participating in CATAPULT has been a natural extension of our commitment to supporting artists in Barbados and across the archipelago for the past nine years.

CATAPULT affirms my belief in and commitment to the Caribbean. Fresh Milk is managing two of the six projects, including the Lockdown Virtual Salons (LVS) and the Stay Home Artist Residency (SHAR), giving us the opportunity to work with six jury members from all linguistic territories in the region, three tech support wizards who made the thirty-two live streams flow easily, thirty-two artists who spoke sincerely about their art practice, sixteen co-discussants who engaged in dialogue with the grantees, twenty-four artists who committed to an eight-week residency, and six visiting critics who participated in virtual studio visits.

RG: What eight items, art-related or otherwise, would you capsule for safekeeping until the other side of the pandemic?

AD: (i) Burt’s Bees chapstick

(ii) Jean Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea

(iii) Bullet blender with ingredients for my daily smoothie

(iv) Paper, pencil, brush, and Victorian rose paint

(v) iPhone with endless podcasts downloaded for many hours of listening

(vi) Agapey chocolate bars with almonds

(vii) Coconut oil with rose oil

(viii) Bush tea (a concoction of circe/cerasee, lemon-grass, bay-leaf, and blue vervain, or turmeric, ginger and lemon)

For more information, please visit:

https://www.instagram.com/annalee.devere/

Photo of Annalee Davis courtesy of Pepe Divi.